22 Mar Will complacency be assessment’s coup de grâce?

By Dale Chu

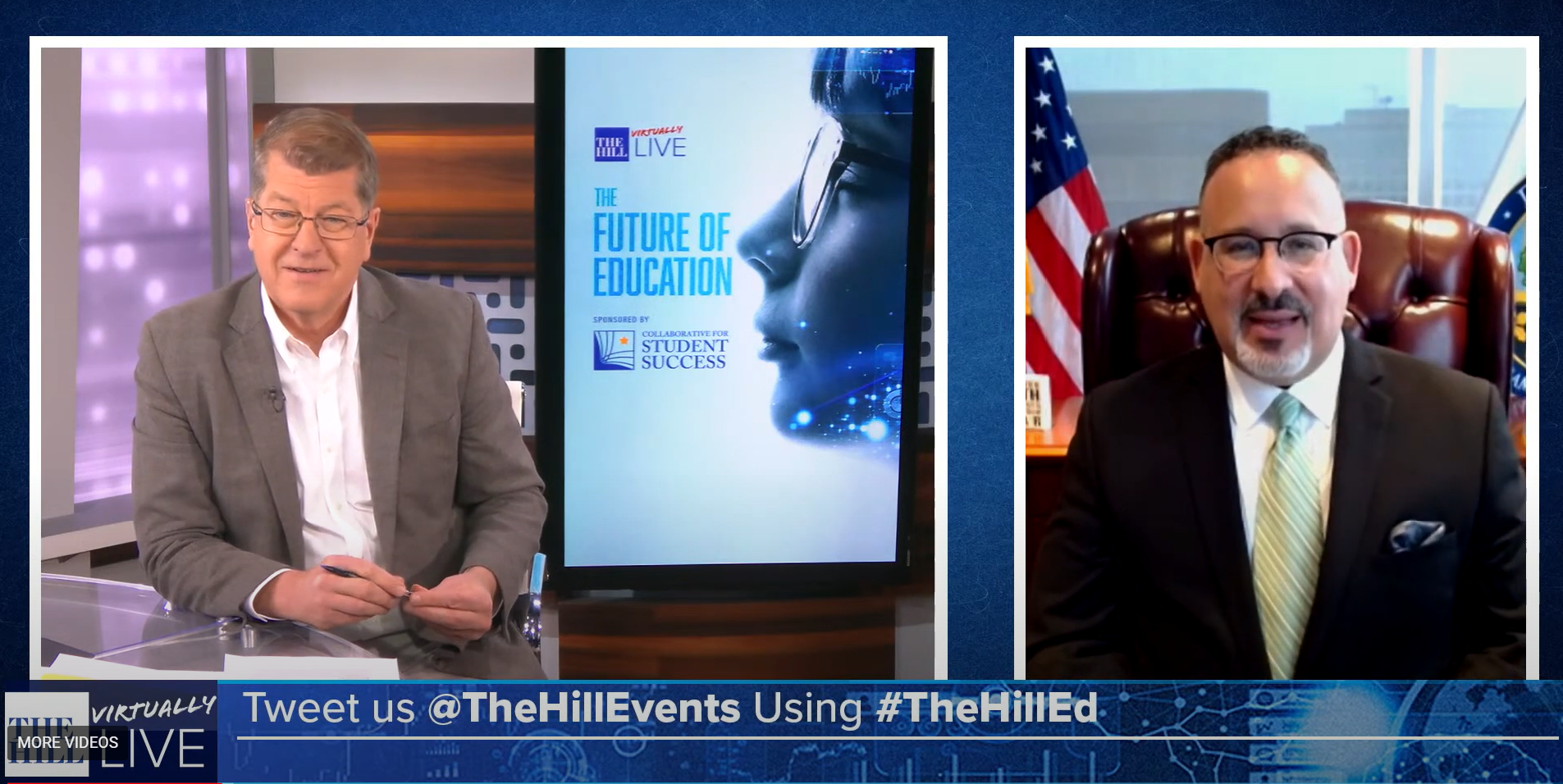

During The Hill’s The Future of Education summit held last week, U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona said that he’s more worried about complacency than he is about the pandemic. He has good reason to be: after two awful years of Covid-constrained learning, students have fallen further behind and the gaps between poor and affluent students have widened. At the same time, many cite the pandemic as a reason for doing away with standardized testing—the primary tool by which we identify these gaps—though by using Covid as cover, these calls come off as being disingenuous.

During The Hill’s The Future of Education summit held last week, U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona said that he’s more worried about complacency than he is about the pandemic. He has good reason to be: after two awful years of Covid-constrained learning, students have fallen further behind and the gaps between poor and affluent students have widened. At the same time, many cite the pandemic as a reason for doing away with standardized testing—the primary tool by which we identify these gaps—though by using Covid as cover, these calls come off as being disingenuous.

I’ll skip past my familiar Chesterton’s Fence argument about why eliminating annual testing would be a big mistake. But the amnesia around why states adhere to this important ritual has helped breed the complacency Cardona laments. In fact, as illustration of how real his concern is, one of the many luminaries that spoke as part of the event made the facile argument that students haven’t really fallen behind at all. Instead of calling what students’ experienced “learning loss,” the speaker suggested the term “learning shift.” I’ll spare you my concerns with this type of wordplay, which is another familiar rant of mine.

Changing the sobering reality facing students—i.e., the facts on the ground—is hard. But changing the words used to describe reality is much easier, and that’s where all of this “learning loss” versus [take your pick] originates. But the more ominous threat comes from those who believe they can change the facts on the ground by simply ignoring the numbers. It’s here that I wish more time had been dwelled upon during The Hill’s event: the essential role of assessment data and its thoughtful application in service of getting more students back on track.

New Hampshire governor Chris Sununu touched upon this. A former engineer and self-professed “data governor,” he underscored the importance of not only how data is collected (i.e., annual state testing), but in how it’s used and using it in the right way. For reasons that are complicated, today’s arguments around state testing data are stuck in a cul-de-sac around whether it’s even worth collecting. That necessarily limits the amount of oxygen available for discussing the use of assessment data in allocating finite resources, which is really where our energy should be spent. Indeed, the use of assessment data is where the emphasis has to be in order to shake the complacency that’s descended upon how education recovery is presently being talked about.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.