By Dale Chu

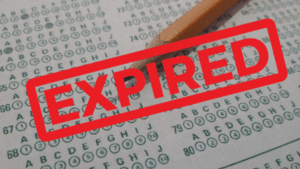

The state assessments happening now in 2022 closely mirror students’ testing experience back in 2002 at the advent of NCLB: they are largely multiple-choice and they are designed to gauge student progress towards a basic level of achievement. In some respects this is understandable. Twenty years ago, policymakers were constrained by the limitations of the tools that were available to assess student academic performance at a large scale. Advancements in technology during the intervening years have since raised fair and important questions about whether states should update their approach to measuring student outcomes.

The state assessments happening now in 2022 closely mirror students’ testing experience back in 2002 at the advent of NCLB: they are largely multiple-choice and they are designed to gauge student progress towards a basic level of achievement. In some respects this is understandable. Twenty years ago, policymakers were constrained by the limitations of the tools that were available to assess student academic performance at a large scale. Advancements in technology during the intervening years have since raised fair and important questions about whether states should update their approach to measuring student outcomes.

One could imagine a staid and coherent campaign to design and deploy tests that are—for want of a better term—more modern. Such an endeavor would be a multi-year, iterative effort, building upon the standardized tests that have been used for decades and addressing the myriad of concerns—ranging from cost to time—that have been raised by teachers and families alike. Importantly, stakeholders would take care not to throw out the baby with the bathwater—recognizing the essential equity guardrails afforded by the current generation of state exams, the tradeoffs involved in jettisoning things too quickly, and developing an intentional plan to phase in new tests while dialing back on the old ones. It wouldn’t be cheap to do something like this, to be sure, but with the massive infusion of federal dollars in response to the pandemic, states would seize the opportunity to deploy these once-in-a-lifetime resources to achieve what might otherwise be unattainable aims with regard to higher-quality assessment systems.

Sadly, this isn’t what is happening. These are a whole host of reasons why states aren’t innovating in student assessments—and they run the gamut from the complexities of test design to the good, old-fashioned political variety. Indeed, despite the well-intentioned efforts to move the conversation forward, most of what passes for innovation in testing these days remains mired in talk rather than action. Because of this, I’ll soon be turning my attention to states on the leading edge—a term I use generously here—of assessment innovation. I’ll examine what some are doing or attempting to do, highlight promising practices, and raise unanswered questions, of which there are plenty. Ambiguity abounds, but one thing seems incandescently clear: states shouldn’t completely toss their current assessment systems until they have a credibly improved alternative in place.