06 May A consensus on diagnostic testing

By Dale Chu

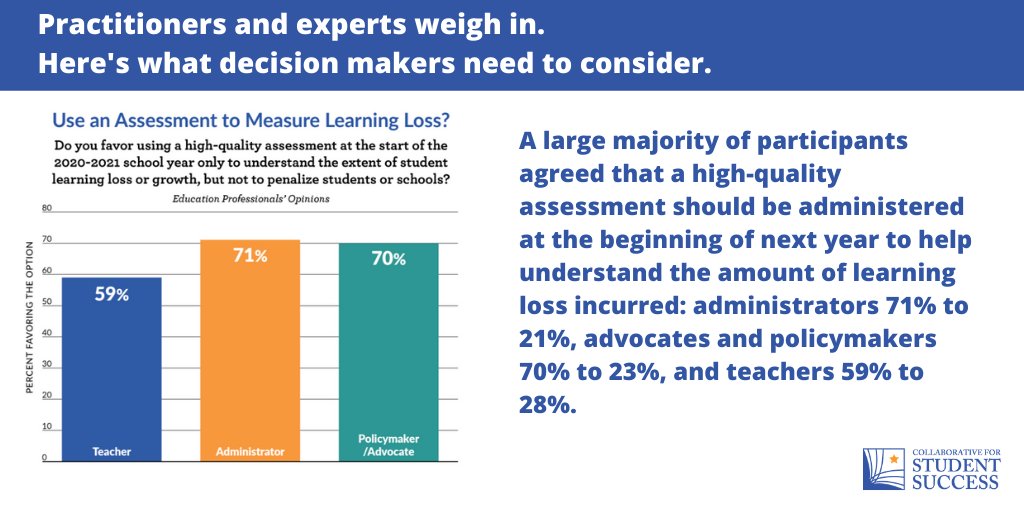

The Collaborative for Student Success recently released the results from a national survey of over 5,500 education professionals, which gauged their perspectives on what schools must do this fall to help students “catch up” from the unprecedented disruption in learning engendered by school closures due to the coronavirus. Notably, the poll showed that diagnostic testing will be more valuable than ever. From administrators and teachers to parents and policymakers, everyone will want to know the extent of the learning loss when students return to school this fall. A high-quality diagnostic assessment can help to pinpoint weak areas and provide actionable data about how to get students back on track.

The federal government can and should help coordinate an effort to help states implement a high-quality diagnostic testing effort when in-person schooling resumes. Absent that, states may be on their own in how light or heavy a touch they use to assess where students are. I just got off of the phone with a state education official who reports that his state is exploring a range of options for diagnostic testing, which includes leveraging publicly released test items and providing them in an easy-to-use format for local districts. They’ve also lined up conversations with a number of assessment vendors that already operate in the state. I imagine similar conversations will start happening across the country if they haven’t already.

The federal government can and should help coordinate an effort to help states implement a high-quality diagnostic testing effort when in-person schooling resumes. Absent that, states may be on their own in how light or heavy a touch they use to assess where students are. I just got off of the phone with a state education official who reports that his state is exploring a range of options for diagnostic testing, which includes leveraging publicly released test items and providing them in an easy-to-use format for local districts. They’ve also lined up conversations with a number of assessment vendors that already operate in the state. I imagine similar conversations will start happening across the country if they haven’t already.

The growing consensus on diagnostic testing is encouraging, but long-term the outlook for state assessment remains cloudy. Establishment forces are poised to storm the assessment bastille (e.g., see Massachusetts); to them, the pandemic is the perfect excuse to eliminate standardized testing and the related accouterment once and for all. And if schools are forced into intermittent closures this fall, expect the already charged testing debate to heat up on whether schools should administer statewide testing in 2021 (and for that matter, 2022 as well).

But testing can’t go away entirely without amending federal law. And it shouldn’t go away until we have a comparable—or better—system to hold schools accountable for student progress and performance. To wit, witnessing some districts decide that remote learning is “just too hard” should serve as an important reminder that public pressure and oversight remain as essential today as when states were first required to implement statewide annual testing under No Child Left Behind.

No Comments