28 Jun Is it time for “forward-looking” assessments?

By Dale Chu

As predicted, two consecutive years without state testing has provided the permission structure for some to begin questioning the utility of statewide standardized assessments. Take California as a prime example, where Uncle Sam afforded local jurisdictions an escape hatch from federal testing requirements via some dizzying verbal gymnastics, which resulted in many districts foregoing state exams altogether. To wit, one local superintendent recently wrote in an Education Week opinion piece that he doesn’t “see much educational value” in the annual ritual of administering the Smarter Balanced test—which he describes as “backward-looking”—and much prefers what he calls the “forward-looking” information provided by his district’s formative exams.

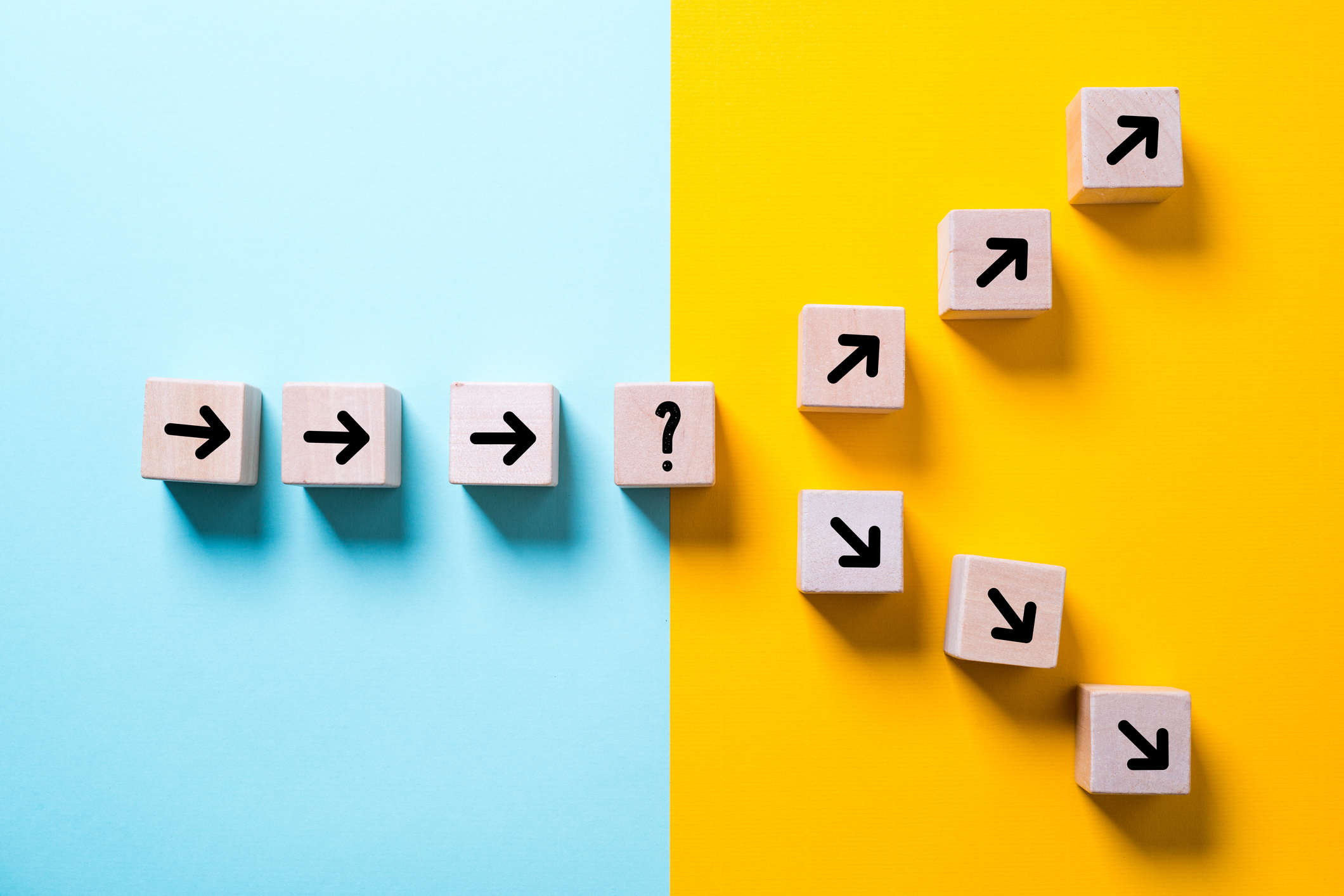

The author’s premise is that “forward-looking” data—provided by i-Ready—is better than the “backward-looking” variety that comes from state testing. Setting aside Michael Horn’s point that by definition data is always backward looking, there’s an allure to the binary, if false, choice presented by the author. I mean, who wants to look backward instead of forward? Obviously, only those who are outdated or stuck in the past, right? But pitting i-Ready against Smarter Balanced—or formative assessments against summative assessments—is both disingenuous and unproductive.

It’s disingenuous because public policy, including the question of how to best carry out large-scale assessment, is about trade-offs. While i-Ready has plenty of advantages, which the author enumerates in his piece, there are simply things these formative exams cannot do. For instance, they cannot provide valid and comparable data across all student groups and districts. They do not have the same level of quality control that enables experts to compare student results across schools and districts over time. What’s more, state tests have credible performance standards as developed by consensus among teachers and subject matter experts.

It’s unproductive because formative versus summative testing is not an either/or proposition, but a both/and. Done well, the two should complement one another, and schools, districts, and states should avail themselves to the benefits of both. Wishful thinking, perhaps, as the national testing debate continues its descent into a zero-sum argument about state tests vs. no state tests. The author clearly favors the latter.

One final note: James Cantonwine, Director of Research and Assessment at Peninsula School District in Gig Harbor, Washington, made a worthwhile observation. He tweeted that the high correlations between the standardized tests the author complains about and the diagnostic measures he clearly prefers suggests something else is at play. Cantonwine surmises that the author’s grievance may be less about the actual test, in this case SBAC versus i-Ready, and more about how quickly the data is made available. If that’s the case, it would be a point of broad agreement as I’ve yet to meet anyone who believes state assessment data shouldn’t be made available sooner.

No Comments